#TheWeekInCareers - Being Human

Do we need to make the case for people in an increasingly tech-dominated world?

Welcome to #TheWeekinCareers! If you are a first-time reader (and congratulations if so, you are now part of a 5200+ strong community!), this newsletter is my attempt at summarising some of the key #Careers-related news from across the #Careersphere each week, along with some of the talking points I feel are worthy of further debate amongst the #Careers community! So, without further ado, on to the news!

At Day 2 of the recent Institute of Student Employers Student Recruitment Conference in Birmingham, I definitely got the sense that some people were starting to get a little saturated with conversations and workshops relating to the subject of Generative AI (and who can blame them!) - I think some of this comes down to the sheer volume of information, thought pieces and commentary out there on the subject (regardless of what industry you might work in) but I believe it also speaks to a similar fatigue that we saw occur during the Covid-19 lockdowns ('If I attend one more Zoom quiz, I'll lose my mind!'); namely, many people are simply exhausted of having to engage in conversations about GenAI, even if they might actually get a lot of value out of the tech itself. For this reason, today's newsletter is all about what it might mean to 'be human' in an increasingly tech-dominated world, and whether we really know what we want for society when it comes to the relationship between people and technology (including - yep, you guessed it! - GenAI). Read on and as always, any comments, feedbacks or provocations are greatly appreciated!

We conclude the newsletter in typical fashion with a jam-packed #BestOfTheRest for you to peruse alongside your weekend coffee (or hot beverage of choice) - as always, I hope you enjoy the newsletter and please do share your thoughts, insights or suggestions related to any of this week's items in the comments thread at the bottom of the newsletter!

Thank you as always for continuing to subscribe, read, comment on and support #TheWeekInCareers! 😁

Being Human - Making the case for people in a tech-dominated world...

What does it mean to 'be human'?

This is the question I've seen bounced around with more and more genuine intent over the past few months, as AI's reportedly unstoppable march to 'superintelligence' continues apace. Naturally, there's a significant incentive for the major AI labs in encouraging policy makers and the general public to believe this change trajectory is legit, but it's also not entirely without merit, given the rate of progress we are seeing with the technology and how quickly we are starting to see AI infiltrate so many areas of our day-to-day lives, from Education and Healthcare to STEM, Journalism, Recruitment, Politics and more:

Read about China's AI policy advisor in the Fanatical Futurist

As Jessica Thornton and Heather Russek from the organisation Creative Futures noted during their excellent Career Development in 2040 webinar with CERIC last year, change often has a long tail and even with some areas of work changing rapidly due to the implementation of AI, there are many others that will take much longer to see the sort of shifts being touted (anyone who has worked for a large organisation or as part of a complex, interconnected ecosystem like the public sector will recognise how long genuine change often takes, particularly from a digital/tech perspective). While this certainly doesn't mean the career development profession should be complacent when it comes to how we help our clients (and each other!) navigate this era-defining industrial shift, it does necessitate an element of nuance and criticality to ensure we are able to separate the headlines and the hype from the practical labour market intelligence and genuine trends that are beginning to materialise (or in some cases, are already happening!)

All of this reinforces the importance of CDPs taking a 'proactive participant' rather than 'passive observer' role when it comes to AI - conversations about what aspects of work we outsource to AI are already becoming a reality in many industries and this is raising questions not simply about upskilling/reskilling but also the nature of work itself and what we want our future societies to look like, in a tech-dominated world. In today's issue of #TheWeekInCareers, I want to do more than just speculate on where AI may be taking us - I want to encourage you all to consider what 'Being Human' means for our work as CDPs and why this matters in our ongoing navigation of the GenAI revolution.

The Anthropomorphic Creep...

As I wrote about it in a recent issue of the newsletter, we're seeing more and more individuals using AI for what we might think of as uniquely 'human' purposes, for example undertaking coaching or therapy. While I'm not going to delve into the practical and ethical considerations of these particular use cases, examples like the above are an indicator of just how easy it is for many people to anthropomorphise AI and treat it as though the advice or guidance it is providing is somehow empathetic and intentional, rather than simply an exercise in performative empathy and pattern matching (and with some models, an element of reasoning based on the data it has access to). Some commentators have argued that this is besides the point - many individuals have their eyes open when using AI, they argue (this Nature article presents some interesting results about perceptions of empathy which could indicate that for now, humans still aren't quite ready to outsource all of our emotional needs to AI), and if an LLM is helping someone move forward with their thinking in the absence of being able to access professional help, surely this is not to be sniffed at?

This is something Sue Edwards and I recently put to the test with a group of students on the MA Career Development and Employability course at The University of Huddersfield, where we explored what sort of role (if any) AI might have within the delivery of career guidance. While the group identified some clear benefits AI could bring to CDPs in augmenting human guidance delivery (providing creative ways to explore different career paths, accelerating research, structuring notes/next steps for clients), a role play exercise using the Hey Pi chatbot did not fill us with nearly as much confidence - as you can see from the video below, while Pi (which is marketed by Inflection AI as an 'supportive and empathetic companion') certainly sounds the part in its initial exchanges with the 'student' in the scenario, it quickly defaults to the sort of Buzzfeed style 'Here are 5 top tips for ____' information giving that clients are unlikely to experience from a decent guidance professional, particularly after sharing vulnerabilities such as a lack of confidence, where genuine empathy and thoughtful questioning, rather than performative empathy and easy answers are often what an individual requires in this situation:

There has been a lot of commentary lately regarding AI's ability to ape human expertise and potentially make 'better' decisions for us in the future (see the article quoted earlier in the newsletter about China's experimentation with AI policymaking as just one mildly terrifying example...) and what's often striking is how open-minded and seemingly blasé many individuals are about this. I'm by no means an AI doomer or sceptic - I've been using GenAI regularly since November 2022 and believe it has got the capacity to potentially improve many aspects of work and human life, as well as making us more creative in the way we approach certain problems - but as David Duvenaud writes in the Guardian (thanks for flagging this piece, Mark Saunders!), it does currently feel like society is sleepwalking into a world where it's just taken as given that AI will be used for everything, whether we believe this is the right thing to do or not:

Better at everything: How AI could make humans irrelevant...

As David Duvenaud notes in the article above, part of the issue with the current trajectory of AI is that it often feels like we are waiting for someone else (e.g. the AI labs, governments, businesses) to make a decision about the direction this technology moves in (which is in itself an interesting parallel to the fears some people have about us outsourcing our thinking to AI!), rather than being active participants in the discourse around AI and its place in society.

Nicholas Thompson of The Atlantic recently posed an interesting question regarding the subject of decision making when it comes to AI - in the video below, he highlights a new study from Microsoft that suggests that AI models, properly set up, can properly diagnose hard medical cases more accurately than humans can and floats an important ethical question connected to this issue that may well end up applying to myriad AI use cases:

If AI models were shown to be 1% more effective than a human when it came to diagnosing your illness, would you let them do it? How about 10%?

Nicolas Thompson - the most interesting thing in tech

This is partly what makes talking about AI such a challenging subject - amongst much of the hype and fluff, there are genuine BIG questions that humanity will need to ask itself over the coming years in relation to how we use this technology, which will have an impact on us all, from 'Do we want AI to take these jobs away from people?' to 'At what point would we permit an AI model to make a decision that traditionally we'd only trust to another person?'

There is undoubtedly more than a little good that AI may be able to do in the world - a cursory glance at the AI for Good website reveals some fascinating use cases (connected to the UN Sustainable Development Goals) that genuinely offer a unique way for us to solve some of the world's most challenging problems, from monitoring biodiversity impact to limit deforestation to AI-enabled 'nudging' / personalised recommendations around product consumption that can help people to reduce individual waste.

Check out the AI for Good website

But all of this must be couched, as the AI for Good site frequently reminds us, with the risks inherent in handing over different elements of our work to AI - it's extremely easy for all of us to frame GenAI as 'just a tool' (and perhaps there is some comfort in this framing) but in truth, there is much we don't yet understand about how LLMs work and what problems they may throw up in the future if integrated into our most vital digital infrastructure. There are a litany of examples out there already to reinforce some of these concerns, here are just three recent entries:

Even AI versions of 'us' can't be trusted - A recent post on LinkedIn from a user of the Google AI coach trained on the works/ethos of Kim Scott (author of the bestselling Radical Candor) flagged that the AI coach in question provided advice that would be fundamentally against the principles found in the author's work, despite the AI being trained in partnership with Kim herself...

Agentic AI misalignment - Recent research from Anthropic into 16 leading AI models from multiple developers in hypothetical corporate environments found that many of the LLMs resorted to malicious insider behaviour (such as blackmail via email or leaking sensitive information to competitors) when this was the only remaining way to achieve the goals they had been tasked with. There is a lot of talk about Agentic AI and its potential at present and plenty of concerns about what might happen in the future if AI agents are somehow misaligned with our goals as humans (either through our own mismanagement of AI, or issues inherent with the technology), all while embedded into the majority of our critical infrastructure...

AI's criminal tendencies - As Stuart Winter-Tear wrote recently on LinkedIn, the idea of LLMs behaving in duplicitous or even 'criminal' ways is no longer simply speculation; we are seeing it reflected in research studies and genuine examples of responses provided by leading AI models (which include the aforementioned Anthropic study but also examples of AI demonstrating sycophantic traits to please users and behaving helpfully whilst being evaluated, while continuing to pursue undesirable or misaligned goals in the background)...

No matter how much of a tech evangelist you might be, these examples indicate just how important it is for humans to be 'behind the wheel' (rather than asleep at it!) when it comes to deciding the role we might want AI to play in our future societies, and crucially, what we would/wouldn't delegate to these tools without human oversight (or if we feel that 'human as final decision maker' is the ultimate red line we would want to build in to our relationship with the technology). As Dominic Atkinson (Stay Nimble) wrote recently on LinkedIn, just because having access to all sorts of data points can help us to understand things in different ways, this doesn't mean our end goal should always be seeking to 'optimise' or 'analyse' to death every facet of the human experience. In many ways, this can lead us to becoming less 'human' in our approach and seeing individuals as a data point to be understood, catalogued and improved, rather than unique beings with their own needs, quirks and personal agency.

All of which segues nicely to the world of work and the (in my view) problematic ideology behind the reported 'AI jobs apocalypse' we've been reading so much about lately....

Headlines and Hype muddy the waters

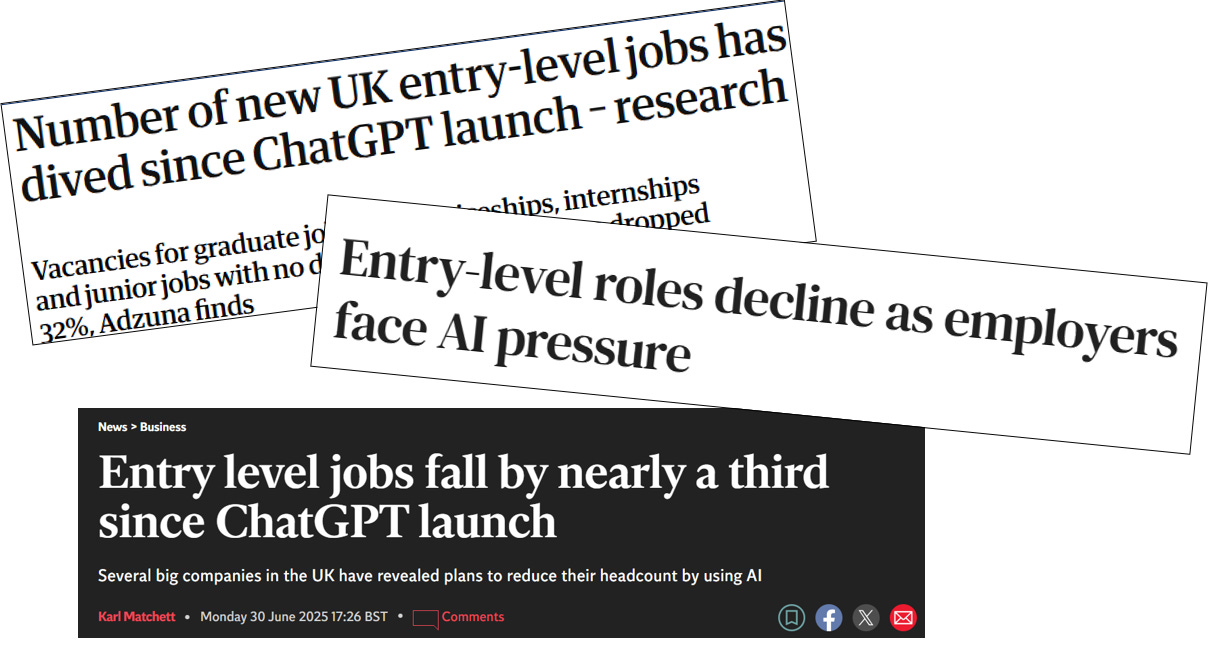

I'll admit, I've been incredibly frustrated this past week by some of the rhetoric around the 'impact' of AI on the entry level jobs market, much of which stems from articles and headlines like the ones below:

The source of many of these headlines was a recent report released by Adzuna, which found that 'vacancies for graduate jobs, apprenticeships, internships and junior jobs with no degree requirement have dropped 32% since the launch of the AI chatbot in November 2022'. This has been added to by comments from recruiting figures like James Reed on Newsnight and has led to a slew of thought pieces, commentary - and yes, scaremongering - from numerous sources, ranging from reflective, critical and thoughtful to the preposterously simplistic.

Number of entry level jobs drops since launch of ChatGPT

There are a few reasons I have a problem with the way these headlines have been framed:

Adzuna themselves have openly shared that they believe the current reduction in entry level roles identified in their data is down to a range of factors beyond simply AI adoption, including many of the global economic shocks and national policy decisions that have taken place in the timespan between 2022 and 2025 - see this post for some thoughtful comments from Andrew Hunter and James Neave at Adzuna that adds much needed nuance to the type of headlines referenced above.

The overall picture about how AI may or may not be impacting the labour market (globally and nationally) is extremely complex - on a call with Lightcast the other day, we discussed how 'AI related job roles' and demand for 'AI related skills' are not evenly distributed across industries/businesses and that it can be extremely challenging to generalise how AI-related change is being experienced from sector to sector, given the jagged adoption and variable level of comfort with the tech amongst both organisations and employees. Just because we are reading about 'AI first' approaches and significant change within the Big 4 and tech firms like BT, Salesforce and Klarna does not necessarily mean that this same change is coming immediately within other businesses.

Other sources, like the recent report from the Institute of Student Employers and Group GTI, paints a different (and more positive picture) of the school leaver and graduate labour market (and no direct evidence that AI is literally taking away student jobs) - while there is no doubt that it's a competitive job market out there at the moment (I hear this reflected by students and graduates regularly), arguably the last thing these individuals need at this point in time is unevidenced scaremongering that their prospects are grim due to a factor they can't see or control (in part because it may not be happening in the way that is being presented in the media!). We absolutely should not want a repeat of 2020/21, when the graduate labour market was on the up but many students and graduates were worried about entering the jobs market, due to headlines about the state of the economy during Covid that proved to be unfounded...

The potential impact of AI on the world of work over time is clearly more than just hype. If we didn't know by 2023 that this technology was likely to herald the next wave of industrial change, we definitely know it now, whether this is reflected in how different governments are investing in AI literacy/education or the AI-enabled business processes we are now starting to see built in as long-term strategies for a variety of employers (even if this isn't always a popular move!)

The potential impact of AI education in schools

But the current impact of AI on work remains murky and uneven, and this is where I feel we in the career development sector need to rethink how we are framing some of our public (and client-facing) conversations around AI. This isn't about us offering warm words of reassurance while the world changes around people, it's about considering how we are framing potential changes in a way that reflects the current reality and possible future/s, rather than a cartoonish extreme (whether positive or negative) that may encourage the sort of knee-jerk behaviours we are actively wanting individuals to avoid (such as investing in costly 'AI training' without a clear idea of what someone wants to get from this and how it might actually be useful for them)

My biggest bugbear by a considerable distance is the market that seems to be springing up around 'future proofing' one's career for a world dominated by AI - as I'll highlight further down the newsletter, there is excellent advice out there about how to navigate the AI-augmented labour market but there are also an awful lot of simplistic narratives being shared (whether through mainstream media, social media or word of mouth), which are demonstrably having an impact on how jobseekers and young people are viewing the current job market.

Take as an example the Guardian article below from Connor Myers, a student at the University of Exeter and intern with the Guardian's positive action scheme, who writes about a graduate jobs market 'devastated' by AI - although the article is informed by the aforementioned Adzuna data on entry level job vacancies, there is so much unprovable speculation presented as fact that it renders the whole piece extremely damaging, which is particularly disappointing given you'd expect a major publication like the Guardian to undertake some due diligence on the subject of their editorials (even if it does feature in the 'opinion' section!). The following are just a couple of examples of potentially influential soundbites that aren't grounded in evidence (at least not in terms of us being able to generalise this phenomena):

The main cause of this (reduced entry level opportunities) is artificial intelligence, which is destroying many of the entry-level jobs open to recent graduates - as reflected in the aforementioned ISE/Group GTI data, there is no demonstrable evidence that this is happening on mass amongst graduate employers, and certainly not at the scale being suggested.

Should a student or recent graduate apply for one of these elusive opportunities, their application will frequently be evaluated and often declined by an AI system before a human even reads it - again, with many graduate employers, it's simply not the case that an AI system will decline a candidate's application before a human has reviewed it, at least not beyond the use of 'knockout questions', which exist within many Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS) e.g. 'Do you have the right to work in the UK?'. Lawsuits like the one currently being launched against Workday are a great example of why many employers are being extremely cautious about the use of AI to make autonomous decisions about candidates, given the potential biases and reputational/legal risks involved.

Read Connor's article in the Guardian

While the lack of fact-checking in the article above is hugely vexing, I can fully appreciate Connor's frustration regarding the state of the graduate jobs market (as he experiences it) and the well-meaning but often pointless advice his generation have been receiving around 'embracing AI' - it must be utterly galling to hear experienced professionals waxing lyrical about the benefits of AI when it's not (yet) their jobs which are at risk, or at least they are in a much more advantageous position when it comes to navigating this change (existing access to networks, professional development opportunities, funded training etc.). As CDPs like Carolyn Parry have observed, there is a dual risk associated with cutting away entry level talent pipelines, both for the individual (limiting opportunities to gain experience/knowledge/skills/mentorship at the start of our careers) and the organisation (impacting succession planning for mid-senior level roles), on top of the general impact on the mental health and wellbeing of career starters we are already seeing writ large in society.

This issue does not simply affect young people, of course - we have a pretty poor reputation in the UK for helping individuals impacted by industrial change to reskill/upskill/navigate these shifts and as is so often the case, it is the individuals who are already advantaged in many ways (whether financially, socially or in terms of other capitals they may possess) that are best positioned to make hay from the GenAI revolution. This is not for one second to diminish the role of personal agency in career development, nor to suggest that many people will simply have to 'deal with' the changes to the world of work brough about by AI but there does come a point where we have to acknowledge that advice like 'be curious', 'educate yourself' and 'upskill now before it's too late' are essentially pretty meaningless nuggets of 'wisdom' at the best of times, particularly if the individual in question doesn't have the time, finances or support to be able to access the relevant opportunities needed.

In part, this comes back to the relentless emphasis we seem to put on the individual in the modern world, when it comes to 'success' - essentially, if individuals lose their job to AI and are unable to find an alternative, this will be because of their laziness, lack of innovation or drive, rather than anything structural that might have been caused by our approach to implementing the technology. As Dr. Eliza Filby notes in her recent Substack post below, one of the big mistakes that is often made during industrial shifts is that nothing is put in place for those who are more likely to be left behind (it can't just be about the individual!) - as she puts it:

'The lesson from deindustrialisation is that the downside to unions is that they are likely to stifle innovation in favour of labour; the downside to employers is that they are likely to supercharge innovation to the detriment of labour...If we expect people to retrain every few years to stay relevant, we cannot expect them to also carry the cost. Especially not when many are already in deep debt from their first round of education.'

The AI job apocalypse is here; here's what should happen

Will the much-touted economic growth promised by AI lead to widespread investment in training or even the implementation of transformative social security systems like Universal Basic Income (UBI) or Universal Basic Services (UBS)? As Raj Sidhu noted in his recent LinkedIn post, if past experience is anything to go on, then we probably shouldn't hold our breath...

And what does 'upskilling' in the age of AI really mean? There are myriad courses that individuals can take to enhance their knowledge, awareness and/or aptitude with AI tools but how do we really know what will be most useful to us? As many commentators have noted, 'AI is a solution in search of a problem' and we're often seeing domain experts get the most value out of LLMs, as they identify creative ways to do the types of tasks they were in many cases already doing, only now acting as a quality assurer or conductor, rather than the whole orchestra. If I work in Marketing, for example, what do I classify as an 'AI skill' vs a 'Marketing skill' when so many of my day-to-day tasks (from initial ideation to content creation to strategy drafting) can now be augmented using AI tools?

All of this is partly to acknowledge that there are no easy answers when it comes to the question of how we prepare ourselves for the different ways that AI may (or may not) change the world around us - pieces like this recent newsletter from Carolyn Parry and the excellent article below from Benjamin Todd in 80,000 Hours are a reminder that the adoption of AI will be a 'jagged frontier' (to use an Ethan Mollick phrase) and that navigating this change will involve an element of future-scoping research and analysis, developing an understanding of what is happening in industries we are interested in (both from a macro perspective and via building connections on the ground) and recognising the things we do that add value to organisations, projects and other people, whether in isolation or in partnership with digital tools.

80,000 Hours: How not to lose your job to AI

I've generally been using the diagram below (created with Napkin AI) as a starting point for framing the topic of 'AI awareness' with the students that I work with (we'll come to the thornier subject of 'AI literacy' shortly...), as I think that as much as possible, we need to encourage individuals to be curious and motivated to explore how AI might change their world over time, rather than paralysed by the fear of a period of change they feel they have no control over and no agency within. There are no easy solutions to the headlines and hype that seem to proliferate on the topic of AI but anything we can do to attempt to dispel myths or promote a more critical approach to interpreting these news stories is surely a fight worth fighting...

If you don't have a seat at the table...you're on the menu

The line above is shamelessly borrowed from Thomas Chigbo, who shared it in reference to the subject of representation within politics and it stays with me to this day, not least due to the increasing relevance it seems to hold in relation to our evolving relationship with AI.

I spoke at the ISE Student Recruitment Conference recently about the assumptions we make about how individuals feel about AI (I have witnessed a huge variation in terms of comfort, competence and ethical positioning on AI from staff and students I work with across the Schools of Arts & Humanities and Computing & Engineering at my institution) and for this reason, I think it's more important than ever that organisations develop an 'approach' to how they work with AI that is more holistic than simply 'how much time/money can we save by using this technology?'.

All this requires an element of intentionality - we're well beyond the 'just experiment with it' phase of GenAI and for most organisations, we're now into the serious business of reviewing IT infrastructure, data governance policies, regulatory responsibilities (see: the EU AI Act), environmental impact, staff training and development and more. We're already seeing businesses like EY take very public positions on their approach to ethical and responsible use of AI (which as I understand it, includes making business decisions on which AI models are used for what tasks, from both a cost-per-token and energy output perspective) and IMO this is something all organisations should be moving towards, if they aren't already.

What I'm in favour of is quite the opposite of organisations seeking to 'optimise' processes and embed AI into every nook and cranny of their business model - for me, it's about developing clarity around how and why we want to utilise AI in principle, with the flexibility to change course as the technology and circumstances we operate in shift. Leigh Fowkes and I have used the Foresee Framework as one mechanism to facilitate conversations in our own organisations about this topic but there are many other models and frameworks out there (Ed: But are they as useful as Foresee? 😉) - the key element of these reflective tools is that they move individuals and organisations from simply talking about AI (an important first step) to taking a more strategic approach to AI adoption, with practical action then being implemented on a local level, based on the different needs or objectives of particular teams, services or professionals. The diagram below provides a very basic example of what this might look like for an organisation, in terms of establishing an 'approach' to AI adoption and implementation:

This process should naturally force organisations to think about the people involved in delivering change related to AI adoption, a topic that often gets wrapped up in the highly nebulous language of 'AI literacy' - as I was discussing with our Head of Digital Skills just last week, the problem with AI/Digital Literacy is that it's often presented as being a baseline/standard that we aim to get everyone up to, when in reality most of us will naturally have 'spiky' digital skills profiles, based on how we need to use technology for our day-to-day work (and as Ethan Mollick noted recently, there is often a mismatch between what people want to use AI for in work vs what it's actually proving to be most useful for...)

The 'critical thinking' aspect of AI/Digital Literacy has been garnering more airtime of late due to studies like 'Your Brain on LLM' and others which have widely been interpreted as proving that AI tools like ChatGPT make you less intelligent through repeated use, even after the authors of some of these studies have come out publicly to challenge this interpretation. As commentators like David Winter regularly observe, AI tools absolutely have the capacity to enhance stupidity and simplistic thinking in individuals who might already be guilty of possessing this mindset and likewise have the ability to enhance, clarify and challenge the thinking of individuals who are already open-minded to this sort of activity. With Google recently overhauling it's AI Education suite and OpenAI seemingly set to follow suit, it's perhaps even more crucial that we avoid focusing too much on the individual usage of AI and consider the big picture around how we are being encouraged to use AI, and in what settings, so that we can challenge these moves based on our understanding of the technology and the risks it could present if applied uncritically in certain situations (whether by a teacher in the classroom or a CEO in the boardroom).

As Professor Michael Sandel outlines below in his blog for the Centre of Humane Technology, while tech leaders may promise us that AI automation will usher in 'an age of unprecedented abundance - cheap goods, universal high income, and freedom from the drudgery of work' - it's crucial that we ask ourselves what different possible futures with AI could look like in practice and whether the prosperity being promised would be shared across society, or concentrated in the hands of a limited number of beneficiaries, as we've seen happen so often in history. The important point here is that as humans, we do not have to simply be passive observers when it comes to the evolution of AI - we have a responsibility in the spheres of influence that we operate in, to attempt to steer AI adoption in a more humane direction, in any way that we can. The tension this will likely cause with businesses, who have a fiduciary duty to generate profit for their stakeholders, may end up being one of the major battlegrounds in the future of AI, as efficiency and productivity face off against policies and approaches that genuinely put humans first.

Is AI productivity worth our humanity?

So, what might genuine AI/Digital Literacy look like and how do we support people to develop these literacies? In many ways, perhaps we'd be better framing the topic as 'human literacy', understanding how to be a thoughtful, kind, reflective and discerning person in a world that is likely to change, change and change again during our lifetimes - as Stuart Winter-Tear noted recently on LinkedIn, acknowledging AI's limitations as a receptacle of knowledge devoid of curiosity, wisdom and the human experience is not really anti-AI at all, but rather, pro-human.

For this reason, I believe our approach to how we navigate AI as a profession, CDPs and people should be decidedly pro-human at all times, focusing on supporting our clients to develop the sort of big picture, systems thinking, critical reflection, self-awareness, research, analysis, interpersonal skills and understanding of the world and its structures that helps them become proactive participants in a changing world, not simply passive observers or worse (in my view, anyway), self-interested individuals whose sole focus is taking advantage of advances in technology at the expense of others. This is something that Alex Zarifeh is currently doing some brilliant work around with his Futures Readiness resources for schools - fostering curiosity, confidence and a critical eye in young people, rather than solely focusing on teaching individuals how to use AI, an already oversaturated market.

Read about the Futures Readiness programme

This is something I'd like to see more of within the career development profession when we hold training and conferences on the subject of AI (Ed: Some news on this front, coming soon...) - bringing together both the applications and implications of AI, so that we are considering when. how, where, why and even if we need to use AI within our work, and how we frame this transparently with the clients and other stakeholders that we work with. I genuinely believe we have an opportunity to be powerful advocates in the AI space as this technology develops over time - not as evangelists, not as sceptics but as guides to apply a career development and career management lens to the tech trend that is likely to inform a significant proportion of our careers in the years and decades to come.

Ultimately, no matter the emphasis on technology, the success or failure of sweeping reforms like the UK government's new industrial strategy will depend on people, not machines, when it comes to delivering on the promises that have been made - in the ongoing hype cycle that is GenAI, it would do us well to continuously reflect on what 'being human' means and making decisions about our use of technology that genuinely puts the welfare of people first.

So, what did you make of all that? Are we really in danger of losing our humanity or is the rise of GenAI simply reflecting who we've been all along? And what can we do to balance the potential benefits of technology with the welfare of people in all parts of society? Answers, as always, on a #TheWeekInCareers postcard! 📬 (Ed: Or more accurately, in the comments thread at the bottom of the newsletter...)

The Best of the Rest: My Hot Picks from the wider #Careersphere 🏆

🚗 LinkedIn: Why it's better to be a driver than a passenger - First up this week, it's a typically excellent blog from Anne Wilson SFHEA (aka The Career Catalyst) on the subject of why it's always better to be a proactive participant, rather than simply a passive observer, when it comes to using LinkedIn. This is a topic that I know many of the students and graduates I work with find frustrating, as much of the advice provided about using LinkedIn can be fairly woolly and nebulous ('Build your network', for example) but gratifyingly, Anne does a great job of breaking down the different ways that individuals can use the platform (self-promotion, sales, sourcing collaborations, connection) and expanding on what the benefits of more thoughtful LinkedIn use can look like in practice, from opportunities to collaborate on paid projects to making professional friends that can enhance both your career and day-to-day life. A refreshing tonic to some of the more generic content on LinkedIn!

🔁 Framing change - As referenced in today's newsletter, there is plenty of change afoot in the labour market, so it's thanks to Marie Zimenoff for flagging this really interesting 'change cycle' tool, which highlights the different stages of change that we often experience in our lives, as well as the actions we typically take at each stage, linked to the colours associated with traffic lights (e.g. Red for the stages of Loss and Doubt, Orange for the stages of Discomfort and Discovery and Green for the stages of Understanding and Integration). It's a useful model to potentially inform careers education, group or individual coaching/guidance sessions and something that could be adapted to different scenarios faced by the clients that we work with.

🤔 What will the NCS/JCP merger look like in practice? - Over to policy next, as FE Week have recently dropped a piece relating to the planned merger of the National Careers Service and Jobcentre Plus, which flags concerns raised by MPs regarding how the money earmarked for the merger is actually going to be spent in practice - the £55 million promised by the UK government was originally intended to fund a “radically improved digital offer” and the creation of a more “personalised” service for jobseekers but as a number of MPs have highlighted, the details of what this will look like in practice remain scant and the lack of clarity something of a concern, particularly given the government's stated intention to move away from a 'tick box' approach to supporting unemployed individuals. This is a really important story for CDPs to stay plugged into and it will be interesting to hear more details as they emerge, particularly regarding the initial outcomes from the first Pathfinder pilot in Wakefield...

🔞 Notes on growing older - Next up, a shout-out to Ian Leslie, author of the Ruffian (one of my favourite Substacks), who has penned a beautifully written piece on the topic of aging. It's some of the most thoughtful writing I've ever read on what can be a challenging subject to tackle - essential reading all round but there are some particularly valuable themes for career development professionals to mull over (regardless of what client groups we work with), especially in the context of 'achievement' and navigating a multi-generational world of work, Well worth a peruse this weekend!

📝 Share your views on pay and conditions for school-based careers staff - We finish this week's newsletter with what some CDPs might argue is a long-overdue survey into the pay and conditions for careers staff working in schools in England - the survey in question is being carried out by the union UNISON UNISON Careers Services and is part of the work currently taking place with the Government to create a new School Support Staff Negotiating Body (SSSNB), which will decide pay, terms and conditions for support staff, as well as taking a new approach to staff training and development. The anonymous survey will help UNISON to find out whether schools are currently following nationally agreed pay scales when they employ careers staff, and if so where on the pay scale they have been placed, as well as how much variation there is in the pay and conditions of careers staff in schools, so if any of these issues impact you, please take some time to complete the survey this weekend!

I'm always keen to hear what people think of this weekly newsletter format (e.g. Is it helpful? Does it add value to what is already out there on LinkedIn? What might make it better/more digestible?) so please do drop me a DM if you have any thoughts!

See you in the #Careersphere next time around for Episode 110! 👋